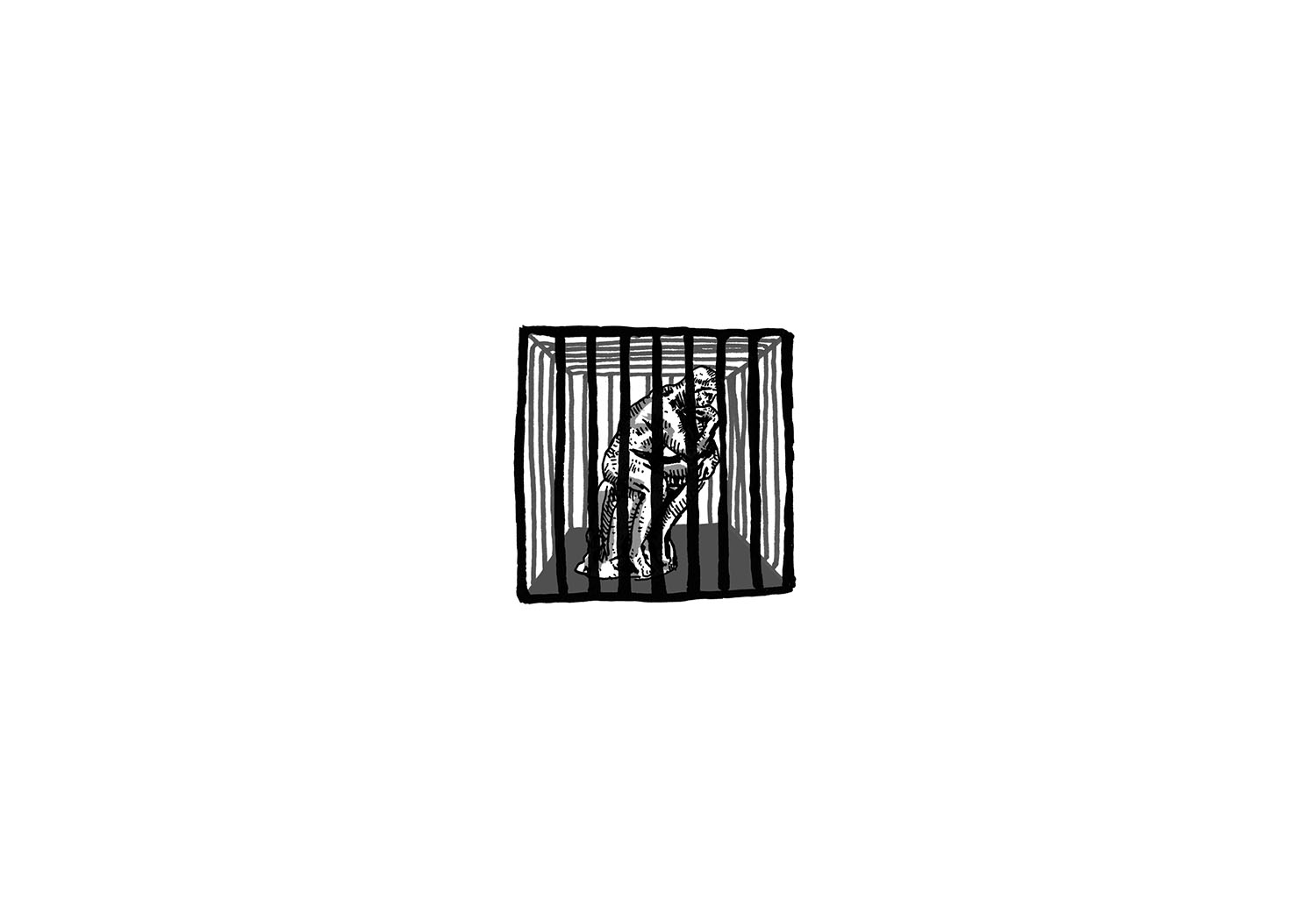

As Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote in his 1762 treatise, The Social Contract, humans are free but are everywhere in chains: literal chains, made of forged steel; or perhaps metaphorical ones, made of gold and silver, illusion, ignorance, indifference, whatever binds and traps us.

Freedom, a Rousseauian would say, is the natural condition of humans, unfettered by debt or obligation in our primal state. But freedom is one of those slippery words that is often defined by its absence. Is a prisoner bound in shackles truly free? Rousseau might say yes: The natural condition has not changed even though the circumstances have. Other philosophers have different takes: Some say that freedom is illusory, still others that freedom is not a blessing but a burden. It’s a concept that philosophers have interpreted, well—rather freely.

Freedom is not contingent on possibility. I am free to flap my arms and attempt to fly, even though, as a flightless biped, I am not really able to fly. I am just as free to fling myself off a tall building in the hope of catching an upward current, although the outcome is not likely to be successful. I am free to buy a villa in Monte Carlo, although my bank account isn’t really up to it. I am free to engage in anything I want to, whether I can pull it off or not.

In that sense, freedom is closely linked to the theological notion of free will, the ability to chart one’s own destiny rather than it being predetermined by some divine agency. If I am free, I am autonomous and self-governing. I may not have all the options I would like, I may be detained or ensnared by sin, but it does not change that central fact. Thus the Siberia-bound anarchist played by Klaus Kinski in David Lean’s 1965 film Doctor Zhivago who, though manacled and chained, declares without irony, “I am the only free man on this train.”

Liberty, by contrast, is not inborn but instead is permitted by law or custom. I am at liberty to remain out past dark, as long as there’s no curfew. I am at liberty to speak my mind, thanks to the First Amendment, as long as I don’t falsely yell “fire” in a crowded theater. (For complex reasons, in some places I am not at liberty to throw myself from that tall building.) If freedom is autonomy, then liberty is bound up in rights and obligations. The two terms are used interchangeably—the 2016 Republican Party platform, for example, uses the phrases religious liberty and religious freedom equivalently—but their greatest difference lies in needing permission to act within the context of some legal or moral structure as against acting on one’s own.

Rousseau held that freedom, although we’re born to it, is realized by what he called the “general will,” all of us being free at once, recognizing that personal interest is best achieved through pursuit of the common good, working for everyone else’s freedom. No one is free unless everyone is free, that is, which gives liberty and freedom urgency in a time when long-oppressed communities are rising up to demand both.